«The first task will be to describe what kind of things we see and what perceptive mechanisms underlie the visual facts. However, stopping at the surface would mean leaving the enterprise unfinished and meaningless».

[Rudolf Arnheim, Art and visual perception: a psychology of the creative eye, 1954; transl. Art and visual perception, Feltrinelli, Milan 2002, p. 26].

«The assertion that extension is limited to bodies is certainly unfounded in itself».

[Albert Einstein, Über die spezialle und allgemeine Relativitӓtstheorie (gemeinverstӓndlich), 1916; transl. Relativity: popular exposure, Bollati Boringhieri, Turin 1967, p. 295].

The tools through which societies represent themselves are formed by structures that are determined by means of a set of more or less latent relationships that exist within a phenomenon. Each structure is simultaneously static and dynamic since in order to exist it needs a space-time reality which corresponds to the place where the process takes place, but the consideration that the processes intervene in the formulation of the structure is equivalent to saying that they also act in the perception of a any data. Data is mistakenly interpreted through established codes that culturally define them as objective and indisputable, i.e. they correspond to the way in which a given company represents itself and its surroundings. The subjective value appears so remote because of the postulates assumed as true or scientifically approved.

At the basis of the perceptive models of societies lie the definitions of time, space and place; our culture has given numerous definitions of these units explaining them through the use of mathematics as an abstract tool to read the data captured by the senses. The abstraction of mathematics presupposes a distinction between these absolute and relative quantities: absolute time is uniform and without any relationship with anything external; relative time is a sensitive and external measure perceived through movement; the absolute space always remains the same and motionless while the relative space is a mobile dimension that we determine through the comparison between the positions of the bodies; the place is instead that part of space that a body occupies by taking on an identity.

If we dwell on the relative meaning of these quantities and place subjectivity as the cornerstone of this discourse, we note that the relationship between the individual-subjective perception and the individual-absolute abstraction leans in favor of the former, overcoming the antinomy between the studies of classical physics and the value of individual perception; the perceived body can take new paths that convey new meanings and approach the model of dissipative structures, or those studies of thermodynamics that go beyond the interpretative rigidity of the classical postulates.

The dissipative system foresees that, under suitable conditions, systems far from equilibrium, when crossed by energy or matter, can lead to a new structure through phases of instability which lead to an increase in complexity where complexity means «a plurality of times, each of which is linked to the others with subtle and multiple articulations»1. In essence, dissipative structures have a sort of memory of their past as they favor some directions over others. This independence of the systems corresponds to that of the perceiving processes and subjects. The relationship between the individual and the surrounding environment becomes osmotic in the way in which the subject sees in a certain way and the perceived structure “shows itself” according to its own directional “choice”.

Restricting the field to the sphere of the visible, the relationship between the eye and the configuration of the structure of the visible data would presuppose that the space of the perceived was intact, but following the previously mentioned theory we affirm that the data can fragment and open up to a place that loses its homogeneity and can lead to electrocution of the never seen. The tool that predisposes the eye to the visible is light which creates an interaction between object and observer, but the microscopic (atomic) nature of the phenomenon cannot be determined a priori in its homogeneity due to the impossibility of simultaneously observing the position and the momentum of the particles, for which every phenomenon has a double microscopic nature (corpuscular and wave). On the basis of the observation conditions we can therefore perceive only part of the structure, either the corpuscular or the undulatory one. Systems, and therefore phenomena, have qualities that are revealed only under certain conditions and when these are manifested, others hide, commonly taking on the characteristic of invisibility.

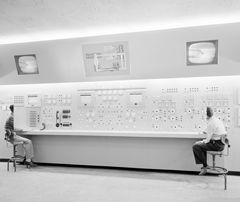

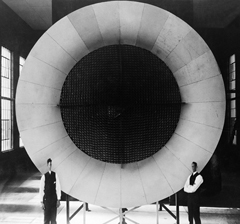

Each image has a latent state that artistic processes often emphasize, reveal or codify readings aimed at interpreting the phenomenon through the representation of a visible whole; sometimes, however, the devices for creating the image affect its integrity with a flaw that marks a paradoxical gash within the visible-invisible antinomy. This is the case of the works of Lamberto Teotino. The artist deconstructs the configuration of the image through a process that refers to Cartesian reference systems.

Reference systems refer to the possibility of describing the position of a body in space by means of a limited number of coordinates; there are four different reference methods which correspond to four different ways of conceiving the movement of a body: the four-dimensional system where by means of four numbers (x, y, z, t) three spatial coordinates and one temporal (in the case of example of the measurement of the space-time universe); the three-dimensional one which has three spatial units of reference (height, length and depth); the two-dimensional one with two units of measurement (height and length) and the one-dimensional reference system (length). The latter, consisting of a straight line on which a point is located, is the system with which Teotino re-establishes a new relationship of tensions within the configuration of the images he examined.

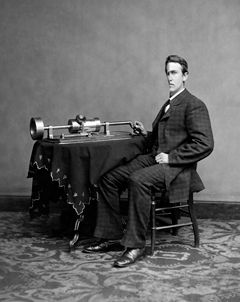

The images, rigorously in black and white, selected by the artist, come from various digital archives that welcome photographic testimonies from the end of the 19th century up to the 1950s. Teotino therefore recovers old archival photographs which he reworks digitally to shed light on what remains underlying the image, on what is submerged by the devices that balance and standardize the construction of photography, but also the relationships and social hierarchies represented . The ploy consists of a one-dimensional ‘cut’, a straight line, which Teotino superimposes on the two-dimensionality of the image and at the same time on the three-dimensionality of photographic depth; the axis of the visible rotates on itself making a portion invisible.

The critique moved by the artist towards the cultural sense given to the perceptive nature of what surrounds us corresponds to the critique towards the articulation of a society which he sees as a codified system of relationships, self-representations and identifications; in this case the invisible root of our culture is combined with the invisible backbone of the forms.

The antitheses between physics and metaphysics, visible and invisible, culture and canonization, are overcome by the use of the one-dimensional reference system in the creative process, which mediates the knowledge of a perception that we can define Gestalt, or autonomously configured, and the experience of the associative devices given by the cognitive structure.

The Cartesian axis in the photographs reworked by Teotino acts forcefully, it manifests itself to break the continuity of the visible and by subtraction and gap it unravels space-time in the plurality of possibilities that matter has to ‘talk about itself’ without conceding to invisibility the statute of oblivion.