Patricio Reig (San Juan Argentina, 1959) graduated in architecture. He’s an autodidact photographer who spent most part of his career in Barcelona and Buenos Aires. He currently lives in Milan.

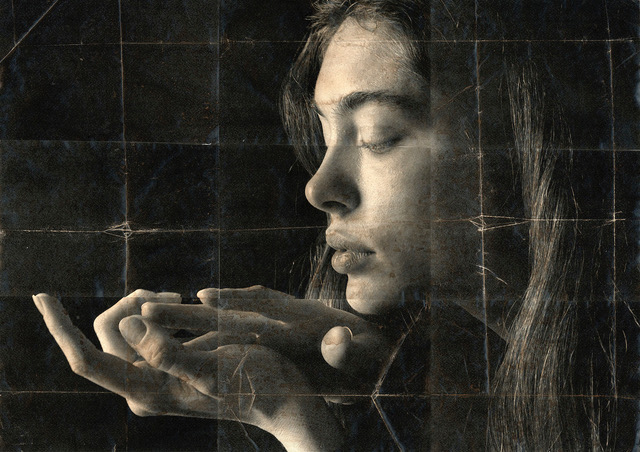

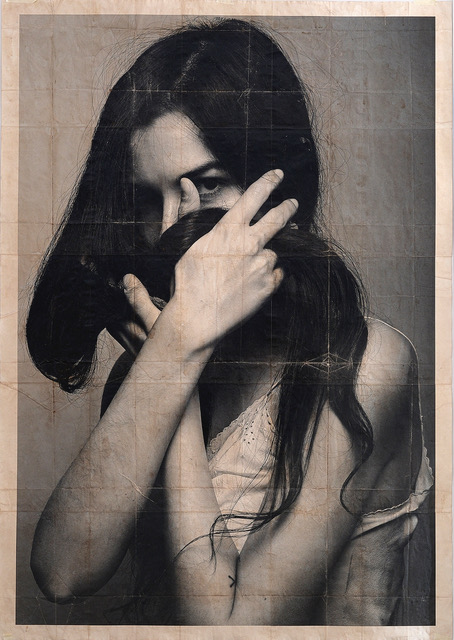

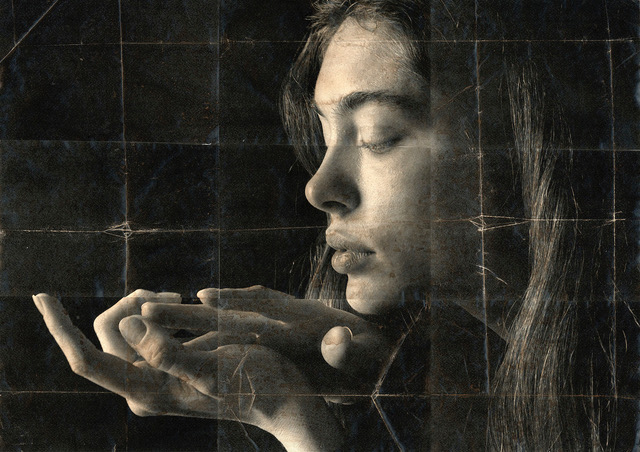

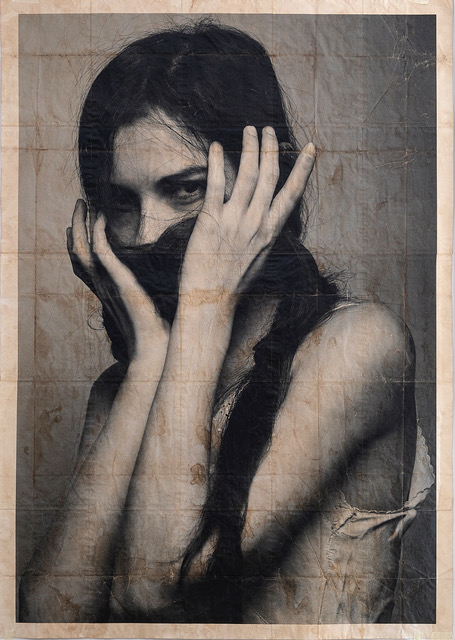

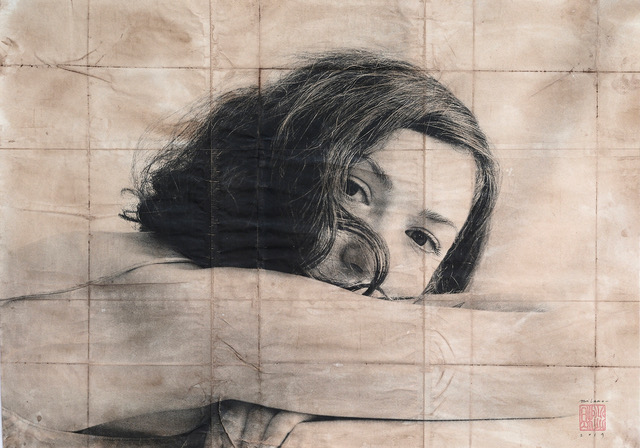

Patricio Reig is mainly interested in the alternative photographic process, like the use of damp collodion, salty paper or stenopeica photo. Over the years he has investigated some new personal techniques: bitumen or sensitive emulsions applied on different kind of paper.

His work focuses on the cycles of life and death and his main themes are nature, portrait, urban landscape or naked portraits.

His artworks has been exhibited in many galleries and museums in different countries.

“I know of no other way halt time. Only photographs can bring life to a standstill and place it in front of me for my contemplation. It is an exercise that should be repeated daily as it makes life easier and allows me to understand a little better the origin and sense of what I mean by reality. For what reason? I often ask myself that question, in the hopes of one day finding an answer.

But this system (which is also a stratagem) is not the prerogative of the visual arts; using words we could just as well curb the brute force of time, sealing it in texts that aspire to eternity.

I irrevocably set out on the path of photography when I was still a youngster. I used to accompany my father, an architect, who worked on social housing projects in the run-down suburbs of Bogotá. He was a member of a team of dauntless enthusiasts trying to improve the living conditions of destitute families, waging quixotic battles against the windmills of injustice and despair. My job was to carry the bag of photographic equipment and change the lens when required. My young eyes were thus present when my father recorded with his Pentax everything that interested him, which is to say a great deal. These were long years of exploration and photo shoots: ramshackle housing, streets on steep inclines, families packed into tiny spaces—and faces, lots of faces. I also remember the smell of these dwellings: smoke, bad food, bare dirt floors.

When life led me to live in Milan, I brought with me a good many of the slides that I had kept since my father’s death, crammed in differently colored boxes, which I occasionally look at with nostalgia. Those eyes, the eyes of the nameless people who looked into the camera back then, continue to stare into mine, into yours, and into those of anyone else who looks at them. With their gaze, which remains fixed on us, they have unwittingly thrown up a barrier in front of time, as if to tell it: “You won’t enter here because you have no place here; we are eternal.” And it’s true: photography, whether consciously or not, gambles on eternity. I suppose that’s what made me understand, very early in my life, the importance of the documentary nature of photography, which allows us to carry with us small fragments of the world so we can possess it, recreate it at a distance, and thus be able to transform it at will. In other words, we can use reality to adapt it to our perspective. And thus I came to understand that seeing is not the same thing as observing, and that the skill of observation is learned by practicing, patiently, like breaking in a mettlesome horse.

For my tenth birthday I was given a 120 mm Diana. Its smell of celluloid is still with me, just like the feeling of the “red” hours spent in the darkroom, where negatives turn positive through the combined action of liquids, darkness, and faint light. The day that magical world was opened before me, a fascination was born in me that has never left me.

For five long years I studied at the School of Architecture, knowing that I would never practice this noble profession, and when they ended, I was given a diploma written in gothic-style letters that satisfied and, above all, reassured my family. What I wanted was to paint, photograph, write, and play music, though without neglecting to study the theories of the great architects, including the Catalan modernists, which I was able to examine with particular interest at the Cátedra Gaudí documentation center in Barcelona.

By working at it each day, I was able to build up a personal photographic vocabulary, a way of proceeding that gave a valid response to all the themes that interested me at the time. I came to realize that a fraction is also a whole, that each part is also an inexhaustible universe that contains a vast amount of information. And that this is also true of all the arts. A portrait can therefore be considered a unique record of an identity, but also as the sum of many other elements. Like an image that also has to be broken into segments, sewn up, or folded without losing its essence. Folding and unfolding, opening and closing, gluing and tearing, removing and adding . . . The quest for the substance underlying the skin of things and beings.”